Interview Insights

02.05.2026

Human + AI technical interview rubrics

The Karat Team

Executive summary

Five years ago, Karat published a resource on how to create structured scoring rubrics for technical interviews. That article remains one of our most-viewed and most-searched web pages.

There are several reasons CIOs and CTOs keep coming back to this content. Rubrics put candidates on a level playing field, allowing leaders to review and evaluate engineers using consistent rating scales. Structured rubrics make it clear which competencies are meaningful for the job, and help extrapolate talent recommendations from those competencies. They also provide transparent and auditable records of the signals used to make talent decisions, which is increasingly critical for regulatory and compliance reasons.

In the human + AI era, the competencies that make strong engineers and the way we evaluate them have changed. So rubrics must also evolve.

Today’s engineers use AI to explore unfamiliar codebases, reason about design tradeoffs, generate first-draft implementations, and accelerate debugging. Simply evaluating whether a candidate can independently produce a correct solution to a bounded problem no longer generates a sufficient signal on talent quality.

This white paper outlines how enterprise CIOs and CTOs must evolve technical skills evaluations and scoring rubrics for the human + AI era. It builds on proven rubric-based evaluation practices while introducing new, AI-native competencies that must be assessed independently and concurrently with traditional engineering skills.

Why traditional rubrics are no longer enough

Historically, technical interviews extrapolated a candidate’s real-world effectiveness from a narrow set of signals:

- How does a candidate reason through a problem independently?

- Does the candidate implement a working solution?

- Can the candidate explain that solution clearly?

Using structured rubrics to observe how a candidate solves real-world software problems allows us to infer other skills. These include dealing with ambiguity, communication, requirements gathering, edge-case analysis, debugging, and optimization, to name a few.

In an AI-augmented environment, that inference breaks down. Today, a working solution to a basic coding question can be produced with far less friction. And because of that, the most valuable engineering work in enterprise settings increasingly happens around the code, including:

- Determining where in a large codebase changes should be made

- Evaluating AI-generated suggestions for correctness and risk

- Making principled design tradeoffs under ambiguity

- Maintaining system integrity, performance, and maintainability over time

Rubrics must evolve to explicitly measure these abilities rather than assuming they are implied.

Core principles for human + AI skills evaluations

1. Separate outcomes from process

In modern interviews, what a candidate produces is no longer sufficient to generate a predictive skills evaluation. Rubrics must distinguish between:

- Task completion: Did the candidate change the system in the intended way?

- Process quality: How did the candidate arrive at their answer?

This requires explicit competencies for navigation, decision-making, evaluation, and justification. And these competencies must be validated regardless of whether the final code was written manually or with AI assistance.

2. Treat AI as an engineering resource

Candidates should neither be penalized nor implicitly rewarded for AI-outputs. This approach builds on our existing “open book” policy that allows candidates to reference Stack Overflow, Google, or other documentation during an interview.

Instead of limiting or over-prescribing AI-use, rubrics should assess:

- When and why AI is used

- How effectively prompts are scoped

- Whether AI outputs are evaluated, tested, and corrected

The goal is not to test familiarity with a specific model, but to evaluate judgment, AI-proficiency, and oversight. This ensures that candidates are properly credited if/when they identify a hallucination and re-prompt the LLM for a new response, and not penalized because the AI (through no fault of the candidate) might take multiple attempts to generate an optimal response.

3. Anchor scoring in observable behavior

As with traditional rubrics, every competency must be scored based on observable actions, and not based on intent or style. If a behavior cannot be reliably observed during the interview, it should not be assumed.

Evolving the competency model: code productivity

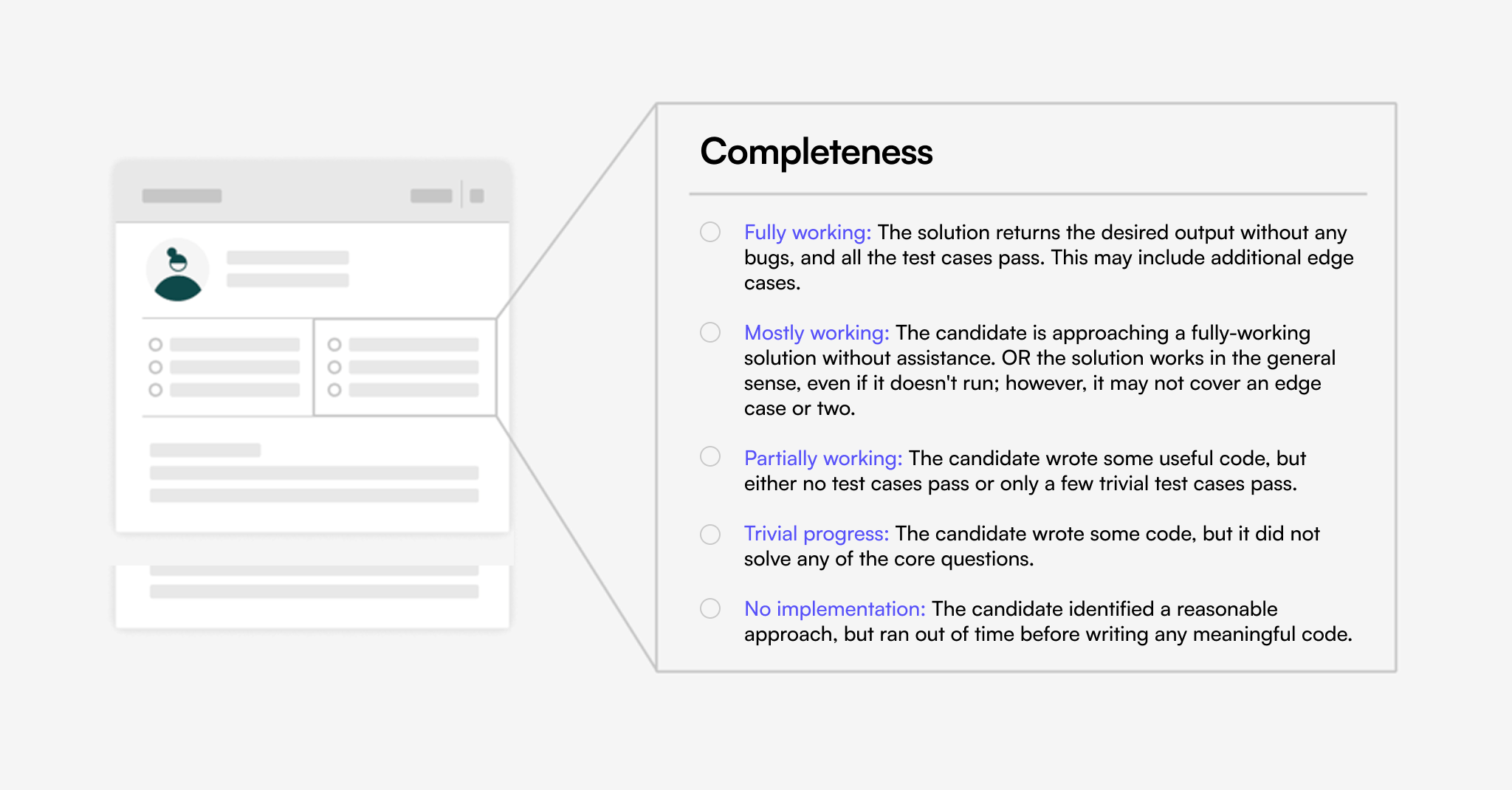

In a pre-LLM world, evaluating coding productivity was relatively straightforward. To what extent did the candidate write code that addressed the task requirements? Our scoring rubrics had a section for “Completeness.” Interviewers were instructed to select one of the following options based on the candidate’s output:

This methodology formed the backbone of most traditional technical assessment formats, including technical interviews, code tests, and take-home projects. While live interviews continue to offer the advantage of robust discussions and follow-up questions that probe candidate understanding, the fundamental point of analysis was still the code a candidate produced and ran.

In the human + AI era, a simple solution to a basic coding question can be generated in seconds. As such, a fully-working and optimized coding solution no longer produces the same hiring signal it once did. Leaders need a more granular rubric to validate the candidate’s approach and separate it from someone who got lucky with a prompt.

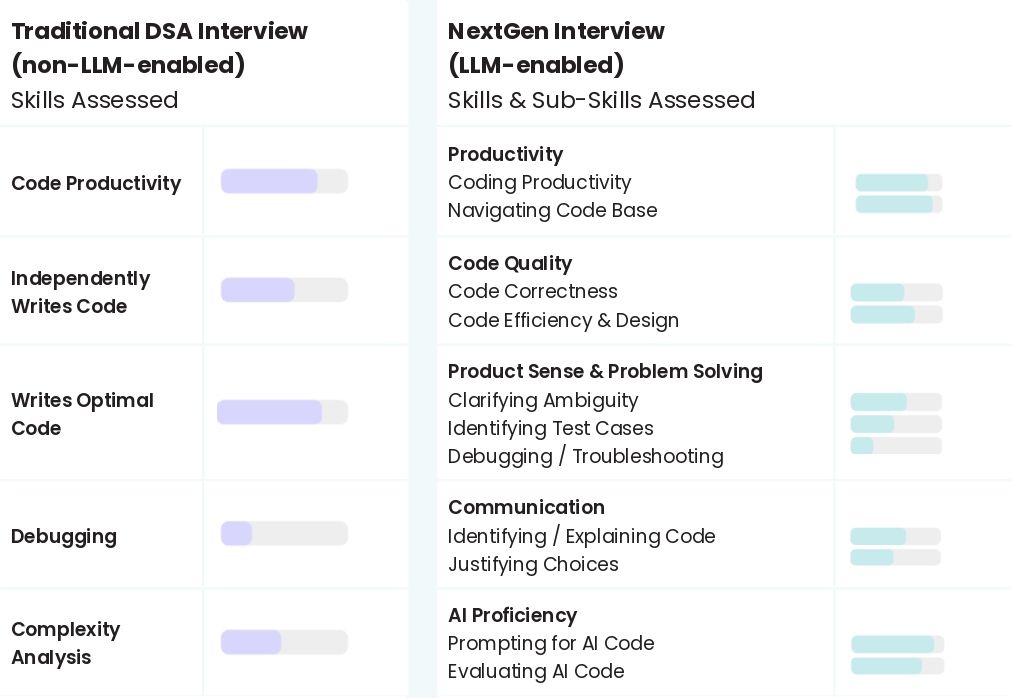

As such, many competencies are augmented with several sub-competencies.

NextGen interview rubrics for the human + AI era

Redefining “Productivity” for the human + AI era

Engineers seldom work in greenfield environments. In enterprise systems, knowing where to work is often more valuable than knowing how to type the code. Rubrics should explicitly assess how candidates familiarize and orient themselves within unfamiliar codebases.

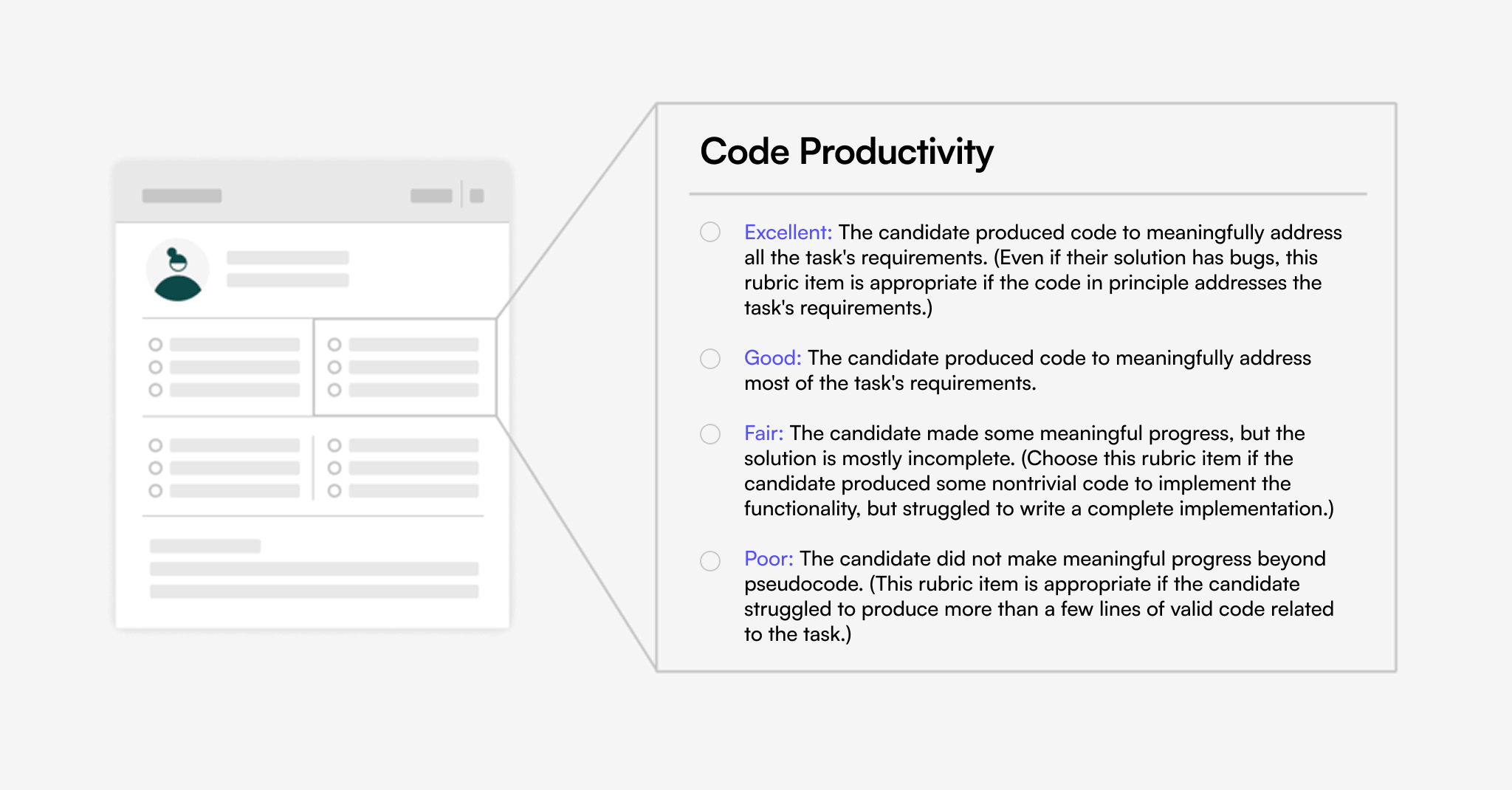

To accomplish this, our NextGen rubric breaks Code Productivity into two sub-segments. The “Completeness” section is replaced by a new measure of Code Productivity, and a new sub-competency that assesses a candidate’s ability to review and navigate a robust codebase while leveraging AI tools.

Sub-competency: Navigating Code Base

Observable signals for Navigating Code Base may include:

- Identifying the correct files, classes, or modules to inspect

- Using tooling (including AI) to accelerate understanding

- Avoiding unnecessary exploration of irrelevant areas

These two scores (Code Productivity and Navigating Code Base) can be weighted based on the role requirements and are combined to create a new aggregate Productivity score.

Updated competency: Product Sense and Problem Solving

Product sense and problem-solving are examples of critical engineering competencies that “lucky” AI outputs might obfuscate in an interview setting. In AI-enabled interviews, it becomes vital to observe and record how effectively a candidate asks questions to clarify and scope the task requirements.

Observable signals and sub-competencies for Product Sense and Problem Solving may include:

- Asking multiple relevant questions about goals or task requirements

- Making reasonable assumptions in the implementation of a task

- Identifying meaningful cases to test

- Proficiently debugging without assistance

New competency: AI Proficiency

High-performing engineers treat AI as a collaborator, not an oracle. Unchecked AI-generated code introduces operational, security, and reliability risks, especially at enterprise scale. Thus, the ability to evaluate code has become even more important than the ability to produce it from scratch. Thus, evaluating a candidate’s AI proficiency requires insights into both how a candidate produces code using AI and how they evaluate it.

Sub-competency: Prompting AI Code

Observable signals may include:

- Crafting prompts with appropriate scope and context

- Using AI to summarize, analyze, or compare code paths

- Recognizing when AI output is incomplete, incorrect, or misleading

Sub-competency: Evaluating AI-Generated Code

Observable signals may include:

- Reading and explaining AI-generated logic

- Running or testing generated code

- Modifying AI output to align with system constraints

Different organizations may tailor the competencies they evaluate and adjust score weighting across roles and levels, but the most important factor is having clear, consistent guidelines for how interviewers score observable behaviors. This prevents conflating competencies and subjective/stylistic choices (i.e., is the candidate actually a “poor communicator” or did they just have an accent that was difficult for the interviewer to understand?).

From rubric scores to workforce strategies

One essential point to remember is that rubrics are not decisions. They are records of observable behaviors. These observations should aggregate into scores that allow candidates’ abilities to be compared on a level playing field.

This allows for flexibility when:

- Weighting decision-making and evaluation competencies more heavily for senior roles

- Allowing multiple “paths to yes” that reflect different engineering strengths

- Explicitly defining red flags (e.g., uncritical acceptance of AI output)

The result is a much richer, higher definition profile of each candidate that independently evaluates core competencies and AI proficiency.

Structured rubrics matter more than ever

AI amplifies variance. Two candidates can arrive at similar outcomes with radically different levels of understanding, ownership, and risk.

Structured rubrics:

- Make that variance visible and auditable

- Reduce reliance on intuition

- Protect against bias introduced by communication style or AI familiarity

For enterprise organizations, they are the foundation for evaluating engineers who can safely and effectively operate in AI-augmented environments.

Conclusion

AI is raising the talent bar by enabling the strongest engineers to create more value than ever before. Leaders are under pressure to cut costs due to AI gains, but productivity gains alone aren’t enough to keep up with competitors. As a result, most engineering executives expect flat or growing headcounts, with hiring and L&D cited as the main strategies for transforming their workforce for AI.

Yet, despite the strategic focus on hiring and the need to maintain or grow headcounts, most orgs aren’t ready to hire engineers with the skills they need for a human + AI enterprise. Research shows that the organizations that use live human interviewers while allowing candidates to leverage the latest AI tools produce the best engineering outcomes.

By evolving competencies, preserving observable scoring, and treating AI as a first-class part of the engineering workflow, CIOs and CTOs can continue to hire with confidence, consistency, and scale.

The organizations that adapt their rubrics now will be best positioned to build durable engineering teams for the next decade.

FAQs

Rubrics

It depends on the format. Karat’s NextGen interviews treat AI as an engineering resource, similar to other documentation or search tools. Candidates are evaluated on how and why they use AI, not on whether they use it. Karat also offers non-AI-enabled formats that evaluate engineering skills independently from AI.

Human + AI technical interview rubrics are structured scoring frameworks that evaluate both traditional engineering skills and AI-native competencies. They focus on observable behaviors such as reasoning, decision-making, and evaluation of AI-generated output, not just whether code works.

Because AI can quickly generate correct solutions, output alone is no longer a reliable hiring signal. Modern rubrics must explicitly measure judgment, problem scoping, and how candidates evaluate and refine AI-generated code.

AI proficiency is assessed through observable behaviors, including prompt quality, the ability to detect incorrect or misleading outputs, testing AI-generated code, and modifying it to meet system constraints.

In enterprise environments, engineers rarely work in greenfield codebases. The ability to efficiently orient within unfamiliar systems and make targeted changes is a strong predictor of real-world performance.

These rubrics are designed for CIOs, CTOs, and engineering leaders evaluating software engineers in AI-augmented development environments.

Executive summary

Why traditional rubrics are no longer enough

Core principles for human + AI skills evaluations

Evolving the competency model: code productivity

Sub-competency: Navigating Code Base

From rubric scores to workforce strategies

Structured rubrics matter more than ever

Conclusion